Serious Play: Design in Midcentury America

|

Fig. 1: Eames storage unit (ESU), Charles (1907–1978) and Ray Eames (1912–1988), ca. 1949. Manufactured by Herman Miller, Inc., Zeeland, Mich. Birch plywood, laminated plywood, enameled Masonite, fiberglass, and enameled steel; H. 59, D. 27, W. 17 in. Denver Art Museum: Funds, by exchange, from Mr. and Mrs. John C. Mitchell II, Calvina Morse Vaupel in memory of Calvin Henry Morse, Mrs. George Cranmer, Charles E. Stanton, Charles Bayly Jr. Collection, Mrs. Claude Boettcher, Dr. Charles F. Shollenberger, Mr. Ronald S. Kane, Frances Charsky, Dorothy Retallack, Mrs. Alfred B. Bell, Charles William Brand, Doris W. Pritchard, Mrs. F. H. Douglas, Mrs. Calista Struby Rees, and Jane Garnsey O’Donnell, 2017.208. © Eames Office LLC (eamesoffice.com). Photograph © Denver Art Museum. |

|

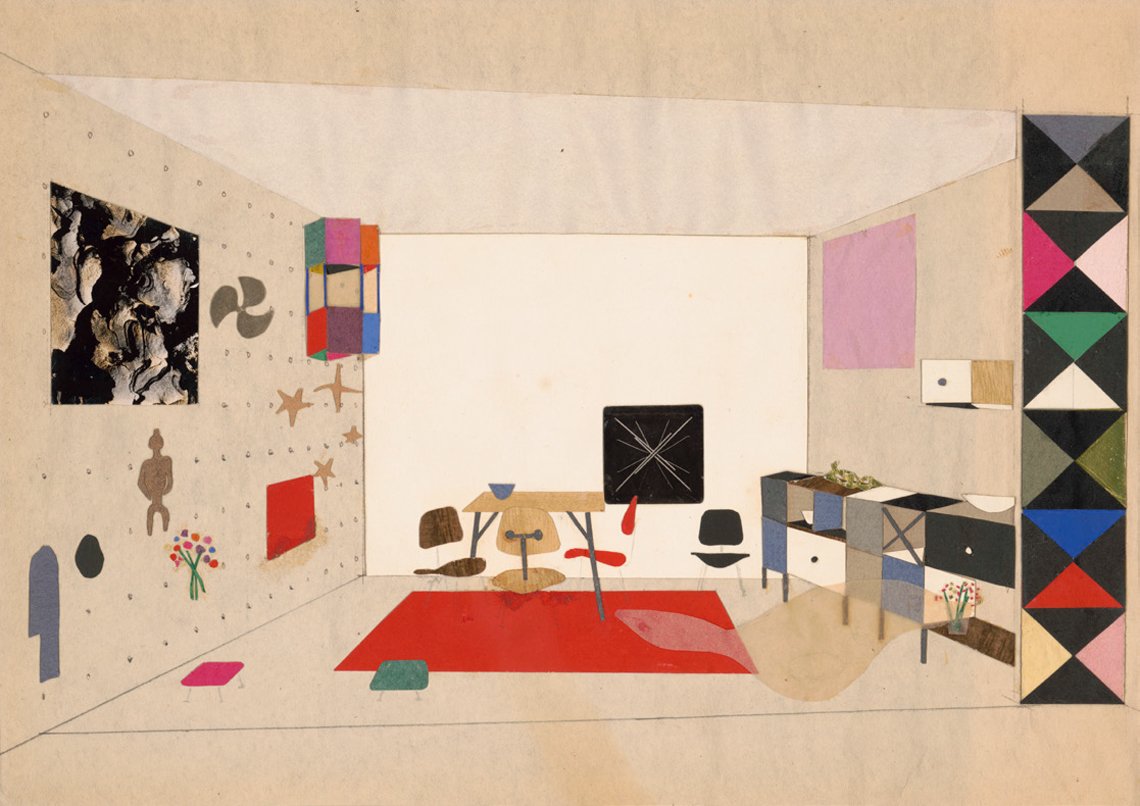

| Fig. 2: Ray Eames (1907–1978), collage for Eames Room, An Exhibition for Modern Living, Detroit Institute of Arts, 1949. © Eames Office LLC (eamesoffice.com). |

The exhibition Serious Play: Design in Midcentury America examines the concept of playfulness as a catalyst for creativity during the era that followed World War II. In this period of rapid change, many successful designers intertwined work and play, leading to designs characterized by creativity and whimsy, qualities also valued in today’s culture. Projects by more than forty designers are organized into the sections American Home, Child’s Play, and Corporate Approaches, and highlight the importance of play as a serious tool for innovation, communication, as well as delight.

| |

| Fig. 3: Advertisement for the Aluminum Company of America’s Forecast Program featuring Alexander Girard’s shelving unit, (photograph by Charles Eames), 1956. © Eames Office LLC (eamesoffice.com). Photograph courtesy of Denver Art Museum. |

One of the period’s most iconic design objects is the storage wall, which designers created to solve a new problem: a booming economy meant Americans were buying more goods than ever. Storage walls and units quickly became prevailing elements of domestic architecture and design (Fig. 1). Designers such as Charles and Ray Eames and Alexander Girard encouraged creativity and a playful approach through arranging objects within storage units, an imaginative way to personalize the home. Similarly, a collage by Ray Eames of unconventional objects organized on a gridded wall reflects this freedom to play with objects in space and apply one’s individuality (Fig. 2). Girard advocated for arranging the home in such a way that helped people be more discriminating in their selection of objects and more playful in their display of them. To demonstrate this, Girard conceived an aluminum shelving unit as a room divider that could be flexibly arranged to meet space, storage, and display needs. He placed within it global folk art from his collection (Fig. 3), when it appeared in an advertisement for the Aluminum Company of America’s Forecast Program. Launched in 1956, the program, in which architects and designers proposed speculative projects, was to investigate new applications for aluminum as an example of how corporations were embracing play.

Designers further supported playful domesticity through whimsical product designs — textiles in exuberant patterns and chairs in the shape of people, for example. With his Marshmallow sofa (Fig. 4) and the clocks he created for the Howard Miller Clock Company, Irving Harper harnessed material and manufacturing innovations to create a new and playful design language (Fig. 5). (Drawings by Harper recently acquired by the Herman Miller archive highlight his design process and are included in the exhibition.) Play and creativity were central to the artistic practice of Eva Zeisel, whose ubiquitous bird dishes and “turnip people” tableware were meant to be entertaining as well as functional. Zeisel’s penchant for whimsical forms also manifested in her simple wooden “aminals,” as she named them, which surprise with a different creature on each side (Fig. 6).

Outdoors, architects and designers imagined sculptural playground equipment that provided for more open and imaginative amusement. Additionally, spaces within the home were newly designated for children’s activities, and corresponding children’s furniture was conceived by leading designers, including Henry Glass and Harry Bertoia. Bertoia’s wire-frame chair was made in a child-sized version. Advertisements (Fig. 8) portrayed the chairs as durable and lightweight — playthings in their own right.

.jpg) |

Fig. 4: Marshmallow sofa, 1956, by Irving Harper (1916–2015), George Nelson Associates, for Herman Miller, Inc. Chrome-plated and enameled steel and fabric, 32½ x 53 x 33 in. Milwaukee Art Museum, Wis., Purchase with funds from the Demmer Charitable Trust and Wayne and Kristine Lueders (M2017.53). Photograph by John R. Glembin. |

|

Fig. 5: Sunflower clock, 1958, by Irving Harper (1916–2015) for George Nelson Associates. Lacquered wood, enameled aluminum, and enameled brass, 29¾ x 3 in. Manufactured by Howard Miller Clock Company. Collection of William and Annette Dorsey. Photograph by John R. Glembin. |

.jpg) | |

Fig. 6: Eva Zeisel (1906–2011), preparatory drawing for “The Two Faced Aminals,” 1950. Courtesy Eva Zeisel Archive. |

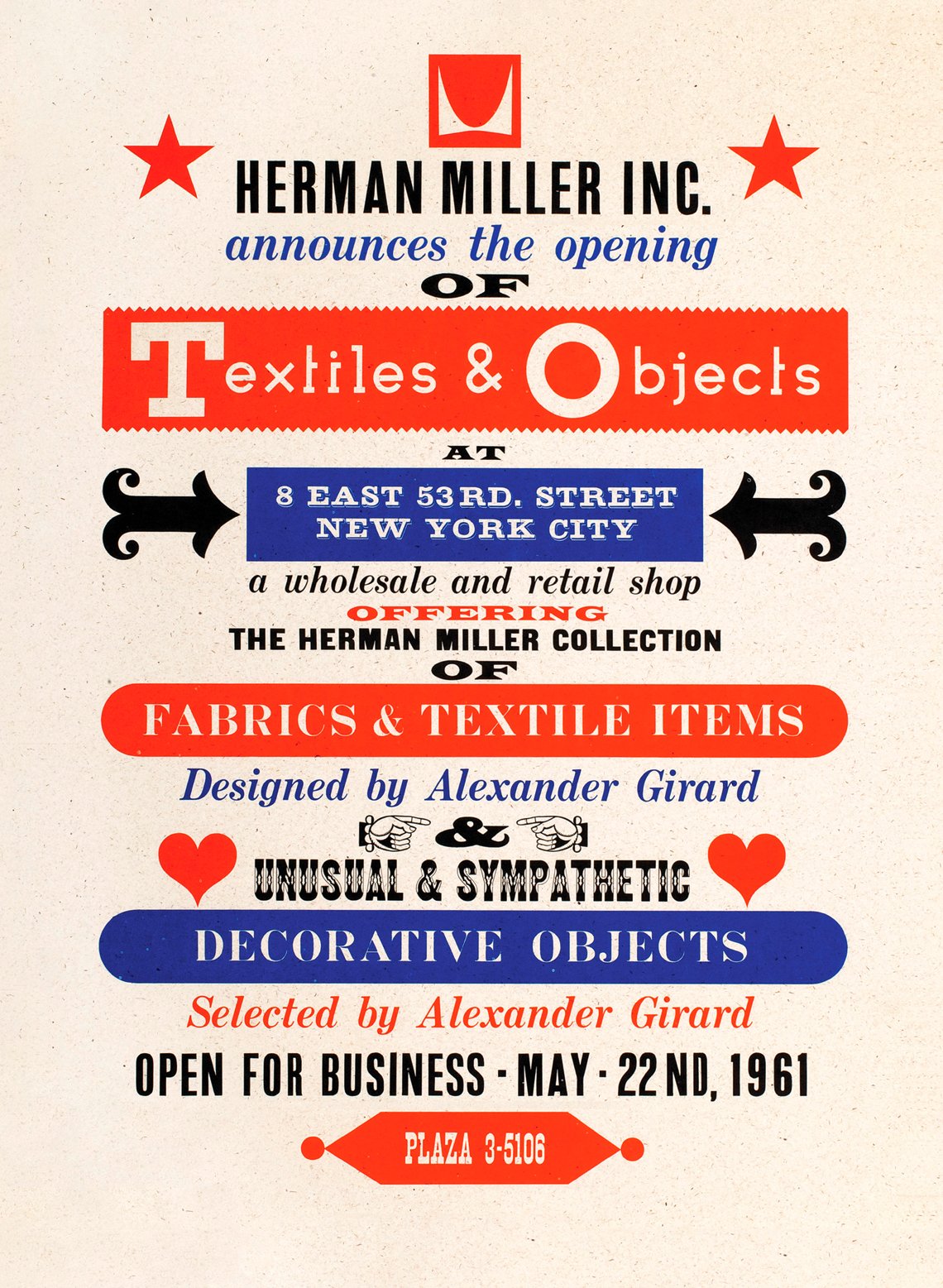

Play was not restricted to domestic settings: segments of corporate America explored new avenues for cultivating distinctive brand identities. In 1961, Herman Miller, Inc. opened Textiles and Objects, an experimental showroom in New York City that sold its contemporary fabrics alongside complementary objects. Alexander Girard worked with George Nelson and Charles Eames at Herman Miller, Inc. As the firm’s textile director, he designed not only the fabrics in Textiles and Objects but also the shop itself. He and his wife, Susan, were inveterate collectors of global folk art (over 100,000 such objects were eventually donated to the Museum of International Folk Art, in Santa Fe), and Girard used folk art in many of his projects (see fig. 2). The showroom projected an image of Herman Miller as a source of modern design enlivened by unique handcrafted items (Fig. 9). While the shop stayed open for only a few years, its legacy is the interjection of whimsy into design retailing in the mid-twentieth century.

|

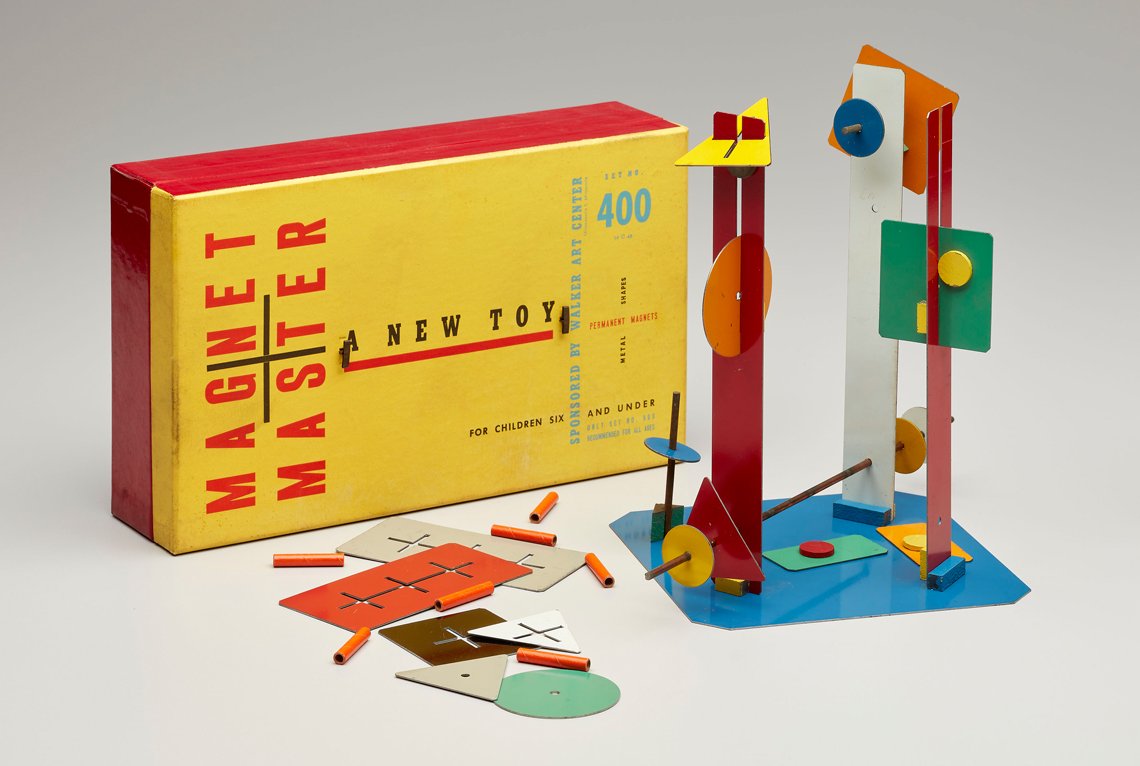

Fig. 7: Magnet Master 400, by Arthur A. Carrara (1910–1991), 1947. Cardboard, offset lithograph, steel plates and rods, and magnets, 2⅝ x 10⅜ x 6¼ in. Milwaukee Art Museum, Purchase, with funds from the Demmer Charitable Trust (M2016.152). Photo by John R. Glembin. |

|  | |

| Left: Fig. 8: Advertisement for Harry Bertoia child’s chairs (no. 425 and 426), ca. 1955. Designed by Herbert Matter for Knoll Associates, Inc. Photograph courtesy Denver Art Museum. Right: Fig. 9: Textiles & Objects announcement designed by Alexander Girard (1907–1993) and John Neuhart (1928–2011), 1961. Screenprint on textured off-white paper. Image courtesy of Herman Miller Archives. | ||

| |

| Fig. 10: Herbert Bayer (1900–1985), Kaleidoscreen, installed in Aspen, Colo., ca. 1957. Aluminum, 7½ x 14 feet, Herbert Bayer Collection and Archive, Denver Art Museum, Col. Photograph courtesy Denver Art Museum. |

When the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) launched the Forecast Program, it invited America’s top architects and designers to explore the material and how it might be used to benefit home and family life. More than twenty leading designers between 1956 and 1960 created prototypes that employed aluminum for everything from housewares to home furnishings, packaging to playthings. Herbert Bayer’s contribution was the Kaleidoscreen, a colorful outdoor aluminum screen that could function as a decorative backdrop (Fig. 10). Through this program, Alcoa expressed the belief that providing opportunities for creative exploration can lead to new trends, directions, and possibilities in design.

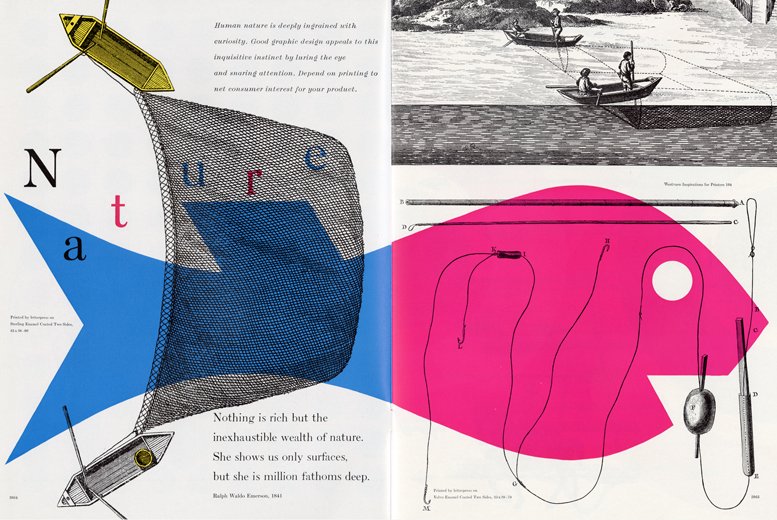

As designer Bradbury Thompson once noted, “There is no creative aspect of graphic design more enjoyable or rewarding than the indulgence in play.” 2 His designs reflect his engagement with play. Playing with his children helped Thomason to conceive layouts for some of the over sixty issues of Westvaco Inspirations for Printers that he designed for the West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company (Fig. 11).

Graphic designer Paul Rand was an integral member of the postwar group of modern designers who believed that design should make the world a better place in which to live. Rand’s advertisements and package designs display bright colors, punchy graphics, and cheerful figures, as in his advertisements for El Producto cigars (Fig. 12). Rand imagined the cigars as various characters, joyfully transforming this adult product.

|  | |

| Left: Fig. 11: Double-page spread by Bradbury Thompson (1911–1995), in Westvaco Inspirations for Printers, 194, published by West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company, 1953. Rochester Institute of Technology, N.Y. Photograph courtesy of Cary Graphic Design Archives, Rochester Institute of Technology. Right: Fig. 12: Paul Rand (1914–1996), “El Producto, For Your King of Hearts” advertisement, 1953–1957. Lithograph on paper. Collection of Merrill C. Berman. Image courtesy of Steven Heller. | ||

Serious Play: Design in Midcentury America is on view at the Milwaukee Art Museum through January 6, 2019, and at the Denver Art Museum, May 5–August 25, 2019. The exhibition is co-organized by the Milwaukee Art Museum and Denver Art Museum.

|

Monica Obniski is the Demmer Curator of 20th and 21st Century Design at the Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, WI.

|

1. See Lotte Johnson’s article in this issue for an example of their toy designs.

2. Bradbury Thompson, Bradbury Thompson: The Art of Graphic Design (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1988), 52.